The State of the Poor

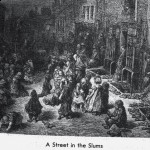

Category: 18th century If Britain’s economy was to continue to expand, the country would have to seek the markets abroad, while holding down living standards at home in order to keep production costs low. The duty of the poor was clear: it was not their business to spend more. They were just more. A detailed and properly documented study of the labouring classes was needed, in order to find out just what their needs were and why they failed to adjust their expenditure to their income. By this time respectable Englishmen were sure that the problem was not poverty but profligacy. Some writers of the time attacked drunkenness, some gambling. Some sought reformation through education, particularly through Sunday schools, which would not interfere with the productivity of the other six days. Others believed it could be achieved through a wider preaching of the gospel, or through legislation and government intervention. But they all agreed on one thing: if the poor is unable to earn a proper living they must concentrate on living more thriftily rather than on seeking higher earnings.

If Britain’s economy was to continue to expand, the country would have to seek the markets abroad, while holding down living standards at home in order to keep production costs low. The duty of the poor was clear: it was not their business to spend more. They were just more. A detailed and properly documented study of the labouring classes was needed, in order to find out just what their needs were and why they failed to adjust their expenditure to their income. By this time respectable Englishmen were sure that the problem was not poverty but profligacy. Some writers of the time attacked drunkenness, some gambling. Some sought reformation through education, particularly through Sunday schools, which would not interfere with the productivity of the other six days. Others believed it could be achieved through a wider preaching of the gospel, or through legislation and government intervention. But they all agreed on one thing: if the poor is unable to earn a proper living they must concentrate on living more thriftily rather than on seeking higher earnings.

Then, in 1797, the detailed and properly documented study which the situation demanded finally appeared, in the shape of Frederick Morton Eden’s epoch-making work “The State of the Poor”. For the first time in history the propertied classes of England could see how the poor lived. With icy precision Eden cut through the cant about profligacy and revealed the truth about poverty. He totted up family earnings and family budgets and showed that for the great majority of the labouring classes there was little enough margin for luxury. Such dissipation as the poor could afford, the occasional bout of drunkenness or the flutter on the lottery, might indeed end by precipitating the whole family into the workhouse. But there was no guarantee that abstention from such vices would keep it out of this grim institution.

Then, in 1797, the detailed and properly documented study which the situation demanded finally appeared, in the shape of Frederick Morton Eden’s epoch-making work “The State of the Poor”. For the first time in history the propertied classes of England could see how the poor lived. With icy precision Eden cut through the cant about profligacy and revealed the truth about poverty. He totted up family earnings and family budgets and showed that for the great majority of the labouring classes there was little enough margin for luxury. Such dissipation as the poor could afford, the occasional bout of drunkenness or the flutter on the lottery, might indeed end by precipitating the whole family into the workhouse. But there was no guarantee that abstention from such vices would keep it out of this grim institution.

For Thomas Malthus, who published his sombre “Essay on Population” in 1798, it was not so much a problem of how the poor lived as one of how many of them lived. He foresaw a world in which the well-meaning efforts of the philanthropists would result in more and more people being kept alive, while the country’s food resources would constantly lag behind this rise in population. Instead of increasing the wealth of the country, capitalism was merely increasing its problems. According to traditional morality, men of property were right to provide more jobs for the poor, right to alleviate their distresses, right to encourage them to live more frugally so that they and their children increased and multiplied; but according to the new morality of Malthus all this was misguided. In the end it must lead to a disastrous crisis of overpopulation. Industrial expansion and moral reform, which the moralists thought had come that men might have life and have it more abundantly, could only lead to death and suffering on an enormous scale.

For Thomas Malthus, who published his sombre “Essay on Population” in 1798, it was not so much a problem of how the poor lived as one of how many of them lived. He foresaw a world in which the well-meaning efforts of the philanthropists would result in more and more people being kept alive, while the country’s food resources would constantly lag behind this rise in population. Instead of increasing the wealth of the country, capitalism was merely increasing its problems. According to traditional morality, men of property were right to provide more jobs for the poor, right to alleviate their distresses, right to encourage them to live more frugally so that they and their children increased and multiplied; but according to the new morality of Malthus all this was misguided. In the end it must lead to a disastrous crisis of overpopulation. Industrial expansion and moral reform, which the moralists thought had come that men might have life and have it more abundantly, could only lead to death and suffering on an enormous scale.

Undeterred by the dark forebodings of Malthus, the new armies of social reformers continued to devise ways in which the poor might live more thriftily, more happily and more profitably. The years of unconcern were over: it was now as fashionable to have opinions about the condition of the working classes as it had once been to have opinions about art and music and literature.

Most of the reformers thought of themselves as liberators, tearing down the old barriers of birth and privilege and charted rights in the name of free enterprise, free thought and free trade. They wanted to create a society based on contract rather than on status, a world in which man’s only duty would be to his employer.

However, behind this apparent concern for freedom there was a new and unprecedented interest in direction and regulation. Jeremy Bentham, who was later to be hailed as one of the prophets of nineteenth-century freedom, was particularly fascinated by the problems of the interaction of work and leisure: one of his schemes concerned a children’s seesaw which would be connected to pumping machinery so that play could be turned to useful purposes. It does not seem to have occurred to him that his invention presaged a world in which play would become more like work, rather than one in which work would become more like play.

Ingenuity of a similar kind had already been applied to animals: since dogs needed exercise and enjoyed running, men were to put them in treadmills beside hot fires so that their continual running could turn a spit for roasting.

Bentham also expanded his ingenuity on the problems of contemporary prisons, where his ideas for constant regulation and organization could be applied more effectively than in the world of free men. His orderly mind was offended by the unhygienic bawdiness and unsystematic violence of prison life. As early as 1778 he proposed to replace all this with something more orderly, a prison in which men and women were to be put to hard labour for “as many of the four and twenty hours as the demand for meals and sleep leave unengaged”. They were to shed the verminous rags which were standard wear in eighteenth-century jails and put on instead specially designed clothes calculated to humiliate them as much as possible. As a final manifestation of orderly benevolence they were to have their names and the addresses of their jails printed on their faces with indelible chemical washes.

By the end of the century Bentham was becoming obsessed with his plan for a “Panopticon”, a circular building designed in such a way that an overseer stationed in the centre could see all that went on in the segments of the circle. Although the Panopticon was particularly suitable for use as a prison, Bentham envisaged it having many other uses as well: factories, schools, workhouses, orphanages and many other institutions could be built in the same way. Wherever there was need for supervision and regulation, whether of work or of leisure, the Panopticon would make it easier and more effective. Just as the Christian moralists aimed to make the working class feel that the eye of God was upon them at all times, so Bentham the rationalist would ensure that the gaze of reason — personified in the overseer — would penetrate to every corner of their lives. By this means, he claimed, it would be possible to gain “power of wind over mind in a quantity hitherto without example”.

As the age of neglect gave way to the age of supervision, more and more men of property found themselves involved in planning society and in overseeing the actions of other men. A large and important section of the population earned their living by regulating the way in which other people earned theirs.

Life among the propertied classes was no longer simply a matter of making one’s way in the world and then enjoying it once it was made; it was a matter of doing one’s duty, of working for work’s sake, of filling the unforgiving minute with the performance of worthwhile tasks.